(An interview with the late Mr. Bob Rogers by Nat Hodge for the 30th Anniversary of The Anguilla Revolution in 1997)

Stout-hearted Anguillian John (Bob) Rogers had been residing and working in the United Kingdom for ten and a half years. Like many others in the mid – fifties he had for a time escaped the economic severity of Anguilla in search of a better way of life for his family and himself. On his return, however, conditions had not improved. The amenities and ‘bounteous living’ he had become accustomed to in England were not available. His frustration gave way to hope when he discovered that a separatist movement was in the making to chart a brighter future for Anguilla. He allied himself to the struggle determined “to help create a better way of living for Anguillians”. In addition to previous and later roles he became a member of a Peace-keeping Committee established on 31st May 1967 to manage Anguilla’s affairs following the expulsion of the St. Kitts constabulary.

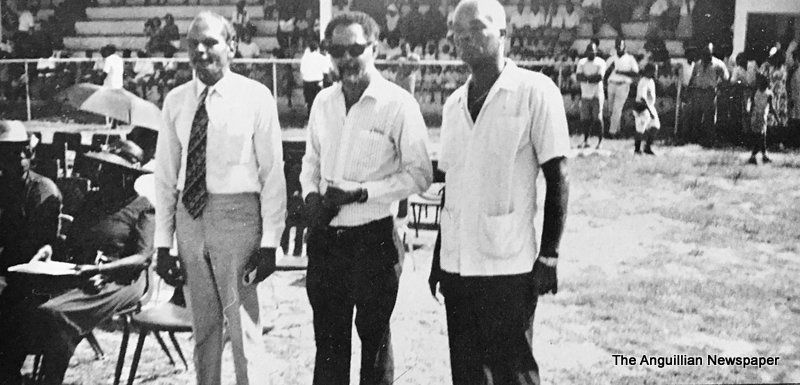

In this interview with Nat Hodge, Rogers a local taxi-driver for thirty years, tells part of the early story of the Anguilla Revolution and his involvement as he remembers and offers his perspectives for the Island’s future.

Ques: What do you remember about the early days of the revolution?

Ans: I returned from England on 7th December 1966. In discussing the future of Anguilla with my cousin Collins Hodge, early in January1967, he told me that Atlin Harrigan and Ronald Webster had started some kind of sessionist movement in the Island Harbour area. I told him we should meet with these two gentlemen and strengthen the movement. I rode a bicycle to Island Harbour where I found Atlin. He told me Ronald Webster had gone to St. Maarten and on his return he would bring him down… We eventually decided on an island –wide campaign to keep Anguilla out of Associated Statehood that was coming in February 1967 and to work towards secession from St. Kitts – Nevis … We held a series of meetings from Island Harbour to West End and collected a number of signatures against Statehood.

By that time Britain had sent a Local Government expert, Peter Johnston, to Anguilla for talks with us. We explained to him that Anguilla had no running water, no electricity, no telephones, no paved roads, no industry, one doctor, two or three trained teachers, and Anguillians traveling to St. Kitts were subject to search and seizure and with these restrictions we felt we were not part of that country. Johnston returned to England and the sessionist movement gained momentum with support from neighbouring French and Dutch Islands and the Virgin Islands. The breakup of the Central Government-organised Statehood Queen Show in Anguilla on 4th February 1967, was one of the first acts of our displeasure.

Later on British Minister of Overseas Development, Arthur Bottomley, visited Anguilla to discuss Statehood and to look at the island’s infrastructure, particularly roads. He drove to the eastern side of the island towards Welches and the road was so bad that he wanted to turn back. The people behind his car told him to drive on and see what they had to endure so he was forced to move on. He then held a meeting at the Community Centre and was accompanied by Paul Southwell, Robert Bradshaw’s Deputy Chief Minister from St. Kitts, and Anguilla’s elected representative Peter Adams. He tried to convince us that Statehood was a good thing. We told him, in no uncertain terms, that we were not in favour of statehood and were not interested in the State’s politics … He said Statehood was here to stay and we told him ‘no way’. We would take the matter to the United Nations … The next thing we know, Bradshaw got them to send a battleship, HMS Salisbury, to Island Harbour saying they had come to put down a riot. The ship left some hours later after distributing sweets to children.

Ques: What in fact was the law and order situation on the island by this time?

Ans: By April and May there was sporadic shooting in Anguilla at nights. They shot up my cousin Atkins Rogers’ house, Hideaway and Wallace Rey’s house, among others. They came up the road where I live and fired shots between my house and my brother’s.

Ques: Who did the shooting and what course of action was taken against them?

Ans: It was the Central Government’s police and what little support Bradshaw had in Anguilla. The shooting was definitely done by them. So next day, Monday, 29th May, we organised a meeting at what is now the Ronald Webster Park. We marched from there to The Valley Police Station. The late Peter Emmanuel Adams delivered a message from the people to the police demanding that they must leave the island bright and early on 30th May because the people of Anguilla no longer felt secure with them around.

Early the Tuesday morning we gathered at the police station. Atlin Harrigan and myself were the first to take one of the policemen to Sandy Ground where he volunteered to leave the island. We put him aboard the WARSPITE which was due to sail to St. Kitts that afternoon to collect the ration for Sombrero Lighthouse.

We returned to the Valley Police Station and one or two more policemen had volunteered to leave and were taken to Wallblake Airport. The ordeal lasted almost all day until about three or four o’clock when the last plane left for St. Kitts with the Central Police…

Ques. How would you describe the effect of this action on the island’s political and economic landscape?

Ans: It was a new beginning for Anguillians who, because of oppression and economic privation, were like the nomads of the Caribbean, with massive migrations to St. Thomas in particular. We felt strongly that if we broke with St. Kitts we would be able to create an economic climate for ourselves and thus develop Anguilla. As you realise today, the fruits of our struggle are clear for everybody to see. Later on in the revolution some of the leaders had strong political ambitions but some of us were more interested in the economics of Anguilla. That is why today, when I hear many people say we have enough, it makes me mad. You see the struggle was to create a better way of living for Anguillans. Surely, after fourteen years of constitutional wrangling, with the British Government, to separate Anguilla from the rest of the State, Anguilla is still not fully-developed and the job market is not controlled by Anguillians. To my mind, all our leaders have failed to that end because it appears as if we ‘cleaned ground for monkey to run on’. This is why sometimes I am known to be controversial because I felt that the spirit of the Revolution was to create a better living for Anguillians; and to encourage them, like the Jews from all over the world, to return home and make a contribution to the economy. It seems as though the spirit of the Revolution has been lost. The Revolution was about economics.

You hear about upmarket tourism and Anguilla being kept for the rich and the famous and that Anguilla does not want any cruise ships. When you look at the people who are saying these things you have to ask where were they on 30th May, 1967? … We were fighting to create an Anguilla that could have been the Israel of the Caribbean.

Ques: But things aren’t that bad?

Ans: Well, we have had some progress but we need more…

Ques: And what about the future?

We need to rekindle the spirit of the Revolution … History will show that the people of Anguilla, and the British Government, can work together. It was the Labour Government of Harold Wilson who was very sympathetic to our cry in 1967. If our leaders would play their part in the partnership we have with the British Government, I don’t see any problem. As a British Dependent Territory the island has a very good climate for foreign investors. People want to know they can come to Anguilla and invest millions and if the Government stills remains good.

If you go independent and you become ‘a banana republic’ you are not going to get any foreign investment; so I don’t see the great argument for anti-British sentiment in Anguilla. I have said over again that just as the West Indies can beat England at cricket, surely Anguillians can get the best of the partnership with the British Government.