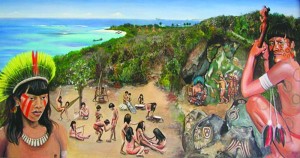

This week we begin a new series, leaving maritime heritage to look at the island’s original inhabitants, the Amerindians.

Around 4000 years ago, Anguilla was discovered by humans travelling by dugout canoes and rafts from South America’s mainland. These earliest settlers were pre-ceramic, meaning they did not make or use pottery but utilised stone-age technology, crafting raw materials including volcanic stones into stone tools.

There is comparatively little evidence of this early group and after a time they disappear from the archaeological record. Around 300AD, a new group came to the area. A culture emerged together with pottery forms and chiefdoms. Known variously as Taino or Arawak, these people named the island Malliouhana. The meaning is not clear although one proposed translation is ‘the place of ritual strengthening of our young men’.

St Maarten Archaeologist Jay Haviser theorizes that during the Early Saladoid period an initial area on St Martin was colonized at Hope Estate, and that during the Late Saladoid period the population grew and eventually fissioned. According to Haviser, some of the population remained at Hope Estate while another part established new settlements at Rendezvous Bay and Maundays Bay in SW Anguilla. Pottery styles are virtually identical on both islands and he believes the two islands should be regarded as a single population. Instead of considering the stretch of water between the islands as a barrier, he argues that it would have served as a highway between villages. He writes that during the post-Saladoid period (AD 600/800-1500) populations continued to expand exponentially and new sites throughout Anguilla and St Martin were founded along with sites on neighbouring St Barths and Dog Island. Around AD 1000 an estimated 2,000 Amerindians lived on Anguilla (roughly the same number of people who lived on the island during the late 18th century). During this pre-historic population explosion, approximately 72% of the St Martin-Anguilla-Dog Island cluster people lived on Anguilla while the other 28% was evenly distributed between St Martin and Dog Island.

During the period, Anguilla may have served as a ceremonial centre for all three islands. Zemis (sometimes spelled cemis) are three pointed religious artefacts central to the worship of the Taíno’s supreme deity of cassava (a root crop) and the sea, Yócahu Bagua Maórocoti.

Caves were ideologically important to the Taíno who believed that all mankind originated from a cave and that the spirits of their ancestors slept inside during the day and came out as bats during the night.

Amerindians believed that the earth was divided into three spheres (caves where humans came from, subterranean waters where the ancestors dwelled and the sky where the gods lived). They carved and painted images of their deities including Jocahu and Juluca (The god of the sea and cassava and the rainbow god [as in Cap Juluca]). Today, petroglyphs remain in the Fountain Cavern (Shoal Bay) and at Big Spring (Island Harbour).

Inside the Fountain Cavern, archaeologists in 1979 discovered more than a dozen petroglyphs. The largest and most impressive by far was a larger than life stalactite carved in the likeness of the Taíno supreme deity Yócahu Bagua Maórocoti. Translated from the Arawak language, the name roughly means ‘the spirit of the cassava and the sea which has no masculine forebear’. According to legend, Yócahu had a mother (who was the goddess of fresh water and fertility) but no father. He was the god of the sea and also the god of cassava.

The Amerindians were a fisher-planter people. In addition to bringing cotton and tobacco from South America, Amerindians also introduced cassava (used as flour) which they cultivated on small plots of land cleared from what was then forest. Today the iguana is the largest indigenous land animal. The absence of large land animals when the Amerindians lived on Anguilla made the Indians rely on the sea for over 90% of their animal protein. They fished both reef and pelagic species including tuna.

According to their beliefs, Yócahu, the god of cassava and the sea, provided everything necessary for Amerindians to live on Anguilla. By all evidence, the golden years’ of Amerindian (Taíno) occupation on Anguilla lasted until the 15th century. Two forces contributed to the decline and depopulation of Anguilla. The traditional view of archaeologists is that from the south, a Carib-speaking group of Amerindians expanded into the region from about AD1200 and at the end of the 15th century diseases were introduced into the region by European explorers. By 1518 a smallpox epidemic which spread from Santo Domingo to Puerto Rico decimated the few remaining Amerindians in the region. Jay Haviser believes that there may have been some overlap between the arrival of Europeans and Amerindians living on Anguilla and St Martin, especially as the islands were colonized relatively late. The explorers who reached the islands in the late 15th and early 16th centuries did not land on the islands and may have missed indigenous populations.

The latest carbon dates recovered on Anguilla date from the 1500s. By the time the English created a settlement in 1650, the Indians had either been removed by the Spaniards to slavery in Puerto Rico and Hispaniola, or more likely, they had died in their villages at Sandy Ground and Rendezvous Bay. Amerindians lacked natural defences to common European ailments. Diseases including influenza, measles and typhoid devastated populations and there is no evidence that anyone was living on Anguilla when it was discovered by Europeans.